handbook for professionals

- INTRODUCTION TO THE HANDBOOK

- CONFLICT AND CONFLICT SETTINGS

- SOCIAL MEDIATION – THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK

- METHODOLOGY

- HANDBOOK TEAM

INTRODUCTION TO THE HANDBOOK

This is a handbook for practitioners such as public servants, NGO staff and members, community workers, youth workers, teachers, non-formal trainers and educators on the use of Social Mediation in a wide range of conflict settings. The handbook can be used by practitioners and institutions in Cyprus and abroad even though it has been developed in Cyprus and within the premise of the Cypriot socio-political reality. Furthermore, part of the handbook’s conceptualisation of conflicts is inspired by the current European reality in a plethora of neighbourhoods and areas which are marred by unemployment, economic dismay and the effects of urbanization, social exclusion and the tension between communities of the ‘majority group’ and other communities such as migrants, refugees and ethnic minorities. As will become evident, the construction and deconstruction of conflict is a central element of the Social Mediation process, with the conflict itself varying in time and place. However, the theoretical backdrop, approach and methodology remain the same. As a result, the handbook can be used by practitioners beyond the Cypriot setting. On this note, it must be underlined that ICLAIM had highlighted the need for such a handbook given our national contextual reality which, in part, is shaped by the political setting (the Cyprus problem) but, also, the social setting which is shared by other European countries.

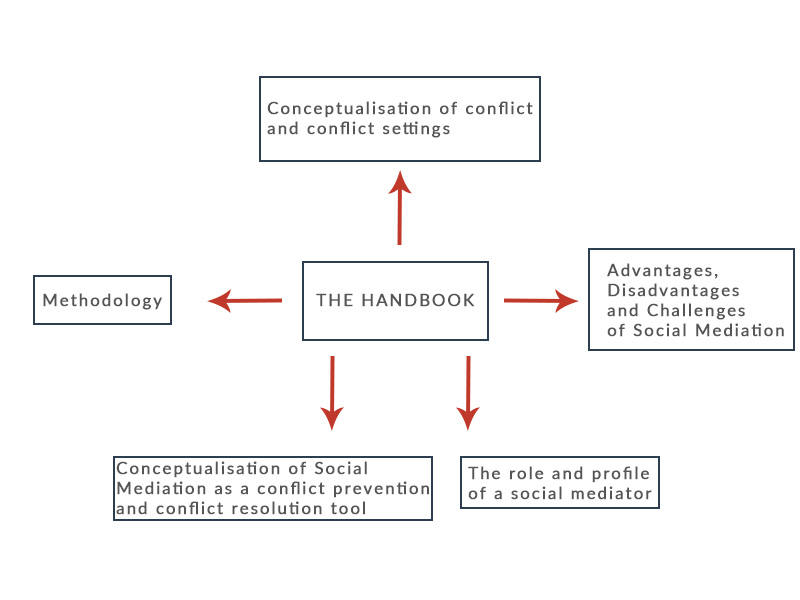

Although there has been some research, predominantly of an academic nature conducted in the field of social mediation, this is habitually theoretical and/or context specific and/or country specific. In addition, there has yet to be a user-friendly resource for professionals wanting to find out what social mediation is and how they can use it in relation to community conflicts. This will be the first handbook with these objectives. To this end, the handbook looks at the meaning of Social Mediation, its characteristics, role and purpose and the community contexts in which mediation can be used. As well as the conceptual framework of Social Mediation, this handbook also seeks to offer practical advice and information to its users by incorporating, for example, case studies in which Social Mediation is a useful and relevant tool as well as practical information on what makes a good mediator. It also contextualizes Social Mediation by setting out the advantages, disadvantages and challenges related to it. For purposes of going beyond a theoretical framework, a series of case studies and good practices are incorporated so that users have the opportunity to develop the knowledge and skills necessary for Social Mediation. In this light, the handbook is moving within the interrelated and interconnected frameworks below:

As will be demonstrated in this handbook, Social Mediation can be used to address a variety of community conflicts. It is significant that the professional or stakeholder working with this method firstly deconstructs the structural foundation of the conflict he/she/it wishes to tackle and the contextual backdrop that exists. For example, factors which are to be taken into account in Cyprus are that ethnic, religious, national or cultural tensions that underlie subsequent interpersonal or group conflicts are affected by one or more of the following factors:

- The country’s political reality and the stagnant process of reconciliation on a community level and/or the limited impact of community reconciliation mechanisms on the island (which is particularly affected by the fact that the conflict has not been resolved);

- The arrival of economic migrants, asylum seekers and refugees for purposes of international protection without the existence of a coherent integration policy.

- The process of globalization and its impact on the make-up of societies and the urgent need for the reconceptualisation of majority-minority relations;

- The lack of or little use or recognition of Social Mediation as a tool to tackle conflicts arising from such settings in Cyprus.

The above contextual reality changes with time and place but the overarching power imbalance and problematic majority-minority relationships that exist in, inter alia, the globalized West are applicable to other countries in which Social Mediation can be used.

Social Mediation as a tool to tackle community conflicts has arisen, partly, because of the emergence of a society composed of different cultures and religions, which has resulted in new conflicts because of a lack of proper communication strategies and integration policies to facilitate peaceful and harmonious co-existence. Instead, the perceived inability of co-existence or the perceived contradiction of values and practices has hijacked the process contributing not only to conflict but also to the rise of right-wing populism in Europe. Community conflicts have also increased because of the increasing socio-economic disparities in certain areas due to urbanization, the rise of unemployment and the deterioration of the welfare state in crisis-stricken countries. Moreover, the emergence of a multicultural society ‘asks for creativity and the development of new concepts, values and practices’ to which Social Mediation can contribute in the short, middle and long-term. Even though this handbook adheres to the aforementioned position, a small note must be made in relation to the choice of wording and, specifically, the use of the term ‘multicultural.’ Although, on the surface, the term multicultural appears to be a positive or, at least, a neutral term to characterise the communities of today’s globalized and urbanized world, this handbook adheres to the term ‘intercultural’ for the reasons set out in, inter alia, the Council of Europe’s Education Pack ‘All Different All Equal.’ The education pack underlines that the term multicultural demonstrates a society composed of a variety of national, ethnic and religious groups that live in the same space but not necessarily together, with difference being considered negatively by the majority, whereas an intercultural society is one where different national, ethnic and religious groups live together in the same space, with difference being considered something positive, an added value to society. This is exactly what Social Mediation seeks to achieve in order to address actual conflicts, prevent conflicts from happening and address a post-conflict setting. In the same framework, the handbook focuses on promoting ‘acceptance’ rather than ‘tolerance.’ The very different ‘other’ that has been established by structural and infrastructural settings as well as mass and new media as having values and practices incompatible to the majority is reframed, refigured and reconceptualised in a society where interculturalism exists and facilitates peaceful co-existence of all its peoples, thereby, limiting the possibility of community conflicts that emanate from the perceived differences of its inhabitants.

CHAPTER 1: CONFLICT AND CONFLICT SETTINGS

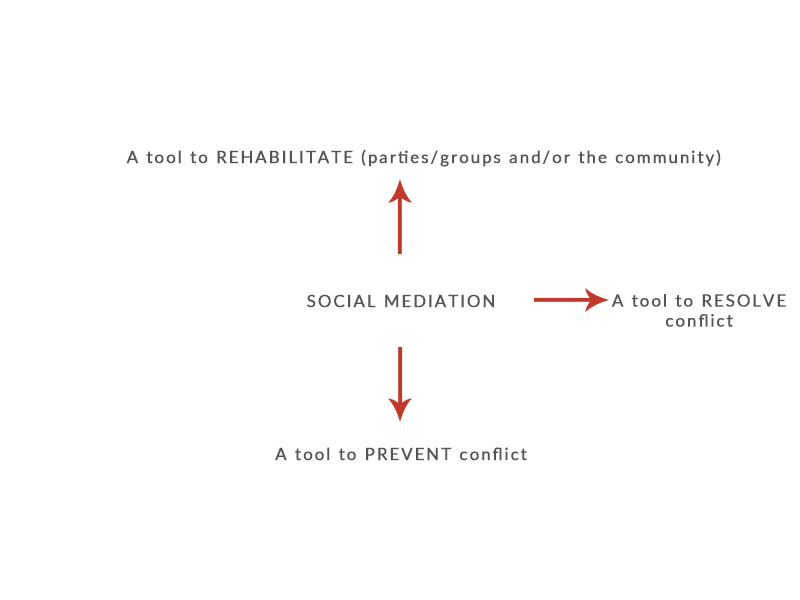

This chapter provides an overview of how conflict and conflict settings are conceptualised in this handbook for purposes of examining the relation and role of Social Mediation as a tool to be used in a pre, current and post conflict setting. It can, therefore, be a preventative tool as well as a reactive tool in terms of tackling a conflict and rehabilitating the parties and their communities.

Conceptualising community conflict:

Conflict is a frequent phenomenon among individuals and organised communities. Professionals who are able and willing to use Social Mediation as a tool to prevent or address conflict must firstly, revisit/reflect on their own vision of conflict and, rather than viewing it as a purely and universally negative reality, instead capitalize on the opportunities arising therefrom to create positive change.

Misunderstanding + Failure to Try to Understand = Conflict

In this light, conflicts may be seen as a manifestation of the needs, worries and/or perceptions of the majority group. In this framework, a social mediator may:

- Address structural issues and thwarted perceptions before these are manifested (pre-conflict);

- Tackle the issues and the conflict itself once the conflict is ongoing;

- Restore the social fabric of the community in a post-conflict setting.

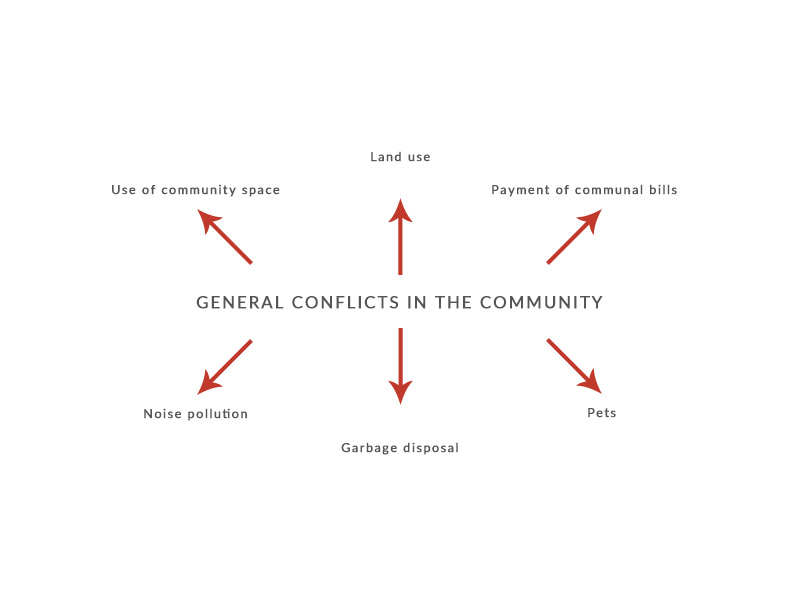

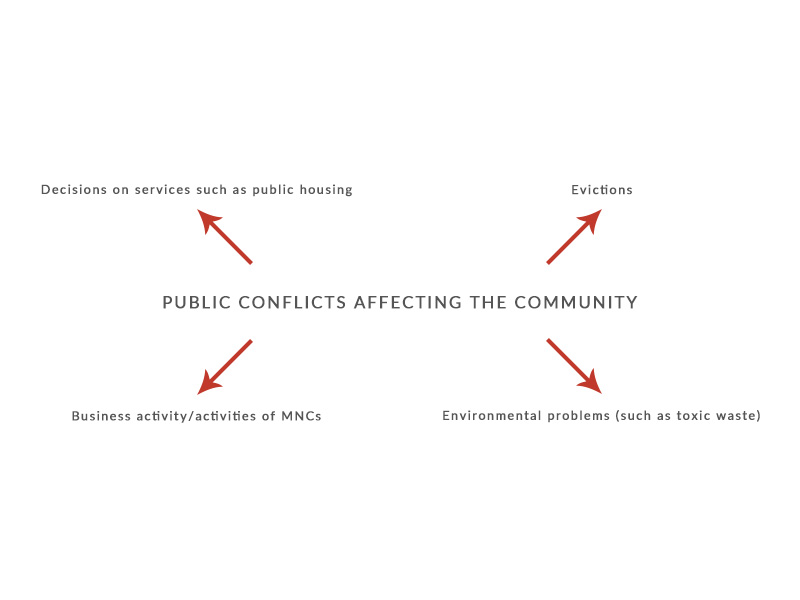

It must be noted that Social Mediation can be used for both interpersonal, group and or structural conflicts in a variety of community settings and on a multitude of levels and seeks to tackle certain conflicts. These are conflicts within the context of individuals exercising their rights stemming from community life; in other words, any conflict that may fall within the term “community.” Community conflicts include those which can occur due to problematic relationships between individuals or groups inhabiting a common space such as neighbourhood conflicts on, for example, behaviour relating to garbage disposal or noise pollution. Community conflicts may also arise out of public conflicts which include evictions and the use of land by businesses. Moreover, and directly relevant to this handbook, as noted above, are intercultural and/or interethnic and/or interreligious conflicts which are conflicts that arise from or relate to particular characteristics such as ethnicity, nationality, religion, culture or ideology. It must be noted that such conflicts are often accentuated by economic factors such as poverty and/or realities of urban areas such as a concentration of persons in public housing who are predominantly affected by unemployment. Prejudices and stereotypes deeply affect these types of disputes.

To summarise, the types of conflicts which can be addressed through Social Mediation are:

It is, therefore, centrifugal that the underlying causes of the conflict, interpersonal, communal and structural, are addressed to ensure sustainability on the impact of Social Mediation activities. Conflicts may arise when two parties or more disagree, or simply misunderstand each other. Conflicts are usually based on the perception of the dominance of one particular perception over the other. The problems arising from conflicts, whether they are intercultural, public or communal, are mainly due to the belief that judgements are static conclusions to which individuals have to comply permanently. The fear of people facing their vulnerability, while closing themselves behind the walls of certainty, undermines the potential which the facilitation of a fruitful conflict possesses. Conflict can be a source for innovation, creativity and transformation, if handled properly.

INTER-CULTURAL/RELIGIOUS/ETHNIC/NATIONAL CONFLICTS IN THE COMMUNITY

Examples of intercultural, interethnic or inter-religious conflict may be either inter-personal or intergroup between culturally, religiously or ethnically-diverse individuals or groups in a particular neighbourhood or geographic area which take the form of violent or non-violent behaviour.

Examples of settings across this form of conflict may occur include:

Political and structural settings: For example, the ongoing political conflict in Cyprus which leads to interpersonal and group conflict between Greek and Turkish Cypriots

Local settings: For example, a neighbourhood or local community which was predominantly inhabited by community members sharing a common cultural, religious or ethnic identity and has recently been inhabited by refugees and/or migrants with different cultural and religious traditions and habits to the locals.

School/university/organizational? settings: Conflicts between members of educational, organisational or other professional structures. This could, for example, be conflicts amongst students at a university which are prompted by racist behaviour.

A social mediator must take into account:

- The diverse nature of the involved community in terms of religion, ethnicity and culture and the dynamic character of its demographics;

- The effects of a stagnant and ongoing political conflict on the behaviour of communities.

CHAPTER 2: SOCIAL MEDIATION: THEORETICAL AND PRACTICAL FRAMEWORK

This chapter provides:

- The meaning of Social Mediation;

- The theoretical backdrop of Social Mediation as a preventative tool, as a tool to tackle particular conflicts but also a tool to rehabilitate parties and/or groups and/or communities of the conflict;

- The role of Social Mediation in rebuilding/strengthening social fabric;

- Relevant stakeholders;

- Beneficiaries of Social Mediation;

- Case Studies of Social Mediation.

What is Social Mediation?

Mediation can be described as a ‘triadic mode of dispute settlement entailing the intervention of a neutral third party at the invitation of the disputants, the outcome of which is a bilateral agreement between the disputants.’ Whilst mediation can be traced back to countries, such as China during the Great Ming Empire (1368-1644), mediation has proven to be resilient and transferable in time, space and context. Mediation can be used to tackle a broad range of conflicts affecting persons in dispute over, for example, employment and family disagreements. Social Mediation is the form of mediation which seeks to deal with conflicts that could, do or did affect social bonds and/or relationships. In this sphere, it is a tool that can work to prevent, tackle and restore conflict and can impact persons on a micro (interpersonal), meso (group and community) and macro (societal) level. It is also a tool that can perceive conflict in a neutral or positive light and, subsequently, mobilise on the existence of the conflict for purposes of enhancing community ties.

A definition for Social Mediation states:

Social Mediation places the parties and their groups and communities at the forefront of the conflict determination, resolution and rehabilitation. To this end, it embraces:

Social mediation as a generic concept and social tool can be used in a plethora of contexts ranging from internet use by children to the integration of migrant communities. This handbook, although embracing the term ‘Social Mediation’ which is the one used in the majority of texts, looks at its use within the structure of a community. As a result, there is an emphasis on the realm and significance of the community at all levels of the process and the conflicts are conceptualised from the perspective that they are manifestations of intolerance and/or prejudice that exist towards a particular group or groups because of their characteristic(s) such as religion or ethnic origin.

Social Mediation is a field that handles conflicts mainly through impartial and independent mediators. The aims of Social Mediation include community self-reliance and individual self-determination. The development of meaningful community capacity and altering conflict patterns are significant Social Mediation tools.

The significance of Social Mediation as a conflict resolution tool lies in its ability to provide access to justice to all people equally. It is a conflict preventative tool “of the people, by the people, and for the people.” (citation?) Social Mediation is regarded as an “empowerment tool” for individuals and communities that seek to take control over their lives rather than being controlled by governmental institutions, such as courts, which may be viewed as inefficient and unfair. Hence, Social Mediation is a tool that allows citizens to resolve their disputes by themselves and build a truly alternative mechanism enabling disputants to avoid prolonged and costly court hearings.

Social Mediation as a pre, current and post-conflict tool:

In cases where conflict is dealt with in a peaceful and non-violent manner, societies will consequently develop and transform. Social Mediation can be ‘preventative in creating social bonds or reparative in repairing them.’ Given that the process is centred on the needs of the stakeholders and their communities, Social Mediation facilitates the establishment of a ‘shared understanding of the past conflict and of how to prevent [it] in the future.’

Social Mediation can be used as a tool to:

- Prevent conflict: By creating a forum and framework of communication and socialisation in a particular setting to prevent the development of, inter alia, prejudices and intolerances and, subsequently, conflict. Within this realm, community ties are consolidated.

- Tackle conflict: By mediating in a particular case involving two or more parties from at least two communities using classical mediation methodology discussed in this handbook. Parties lie at the epicentre of the identification of the causes of the conflict, the deconstruction of the conflict itself and the process of resolution. The aim here is to tackle the conflict itself but, also, to the extent possible in a particular series of mediation activities, also to tackle the underlying structural causes of the subsequent manifestation of the conflict to ensure sustainability of the intervention. This objective is further achieved in the rehabilitation stage.

- Rehabilitate parties/groups/communities after a conflict: Following a particular incident which appears to be resolved, to continue working with the community (and not just the parties involved in the conflict) for purposes of tackling underlying structural causes which led up to the conflict.

More on the methodology used for the above three frameworks (preventing, tackling and rehabilitating) is provided in the next chapter.

The Social Mediator

A social mediator works with the parties involved in the conflict as a third and independent party to the reconciliatory process. He/she aims to solve the conflict and additionally tackle any prejudice that might re-ignite troublesome conduct and cause the parties to relapse into conflict. A social mediator may also, where appropriate, work with bodies such as local authorities, NGOs and grassroots organisations which are directly relevant to the issues at stake. For example, in a case of ongoing violent and non-violent behaviour in a neighbourhood inhabited by locals and refugees (with the conflict arising due to the perceived difficulty of the two groups cohabiting) a social mediator may involve:

- NGOs working with refugees;

- Competent departments of local authorities;

- Community leaders.

A social mediator will reconceptualise the ‘differences’ of the groups and transform them into opportunities for development and improvement for the community members and the community more generally.

The Role of Social Mediation in Rebuilding/Straightening Social Fabric

Social Mediation aims to recreate the fabric of social bonds. The role of Social Mediation includes the construction and rebuilding of a social fabric. Social fabric may be defined as the bond shared between individuals within a community. Through Social Mediation, social fabric is reconstructed. This is because Social Mediation seeks to resolve disputes in a community by incorporating the need to tackle the structural causes of a particular dispute. Once a dispute is resolved, the parties will have a better understanding of each other’s views and beliefs. Thus, individuals would no longer view a lack of a common territorial, cultural or social background as a barrier to achieving common ground. Social Mediation facilitates the formation of healthy co-existence, relationships, coordination and interaction across different social groups in a particular community.

Direct Beneficiaries of Social Mediation in a Community Setting

- Members of various ethnic communities within Cyprus such as: the Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, Maronites, Latins, Armenians and Roma as well as European and non-European nationals.

- Students

- Refugees

- Asylum seekers

- Migrant workers

- LGBT

- Vulnerable and marginalised groups in general

Stakeholders of Conflict Mediation

- Educational institutions

- Non-governmental organisations

- Legal practitioners

- Other professionals such as social workers and community workers

- UN Peacekeepers

- Community leaders

- Religious institutions

- Governmental institutions, etc.

CASE STUDY I

Background

This is a case involving a dispute between a Kurdish student, who has recently obtained refugee status, and a Cypriot student. In Cyprus, refugees and asylum seekers still face various forms of xenophobia and discrimination by citizens and governmental bodies. This is arguably a result of the ineffective integration mechanisms for inducting refugees into society and the misinformation on refugees disseminated to the public by the media and other outlets. Hence, refugees are frequently faced with challenges in society as a result of their status. In this case, the Cypriot student referred to the Kurdish student as a criminal and told him to go back to his country after a football match which involved both of the disputants on opposing teams, leading to an argument between the two parties and a violent episode in which a total of 4 people (including the initial two students) were involved. In addition to the two parties directly involved in the initial conflict, the other people were members of both football teams, some of Kurdish and other refugee origin and others Cypriot. The football match, the argument and the violent episode occurred on campus. In order to resolve this dispute, various mediation techniques can be applied, drawn specifically from Malaysia, South Korea and the United States.

Resolving the Dispute

In cases as the one described above either the Facilitative Mediation Process or the Evaluative Mediation Process can be chosen:

In the Facilitative Mediation Process, the mediator does not direct the parties to a particular outcome but, instead, facilitates the entire process from the identification of the issues until the final resolution. During this process, the majority of sessions (apart from the first one or two introductory sessions between the mediator and each side individually) are composed of the mediator and all the parties. The Evaluative Mediation Process is different in that there are more sessions with the mediator with each side individually and the facilitator is more directional as to the outcome. This process is used, for example, when there are obstacles, such as the sincere intention of one or both sides to reach a solution and, thereby, more direction is needed by the facilitator. It could also be used when the actual meetings of the parties escalate in non-constructive sessions and, therefore, the facilitator needs to spend more time independently with each side. In the event that the parties do not want to meet face to face, shuttle mediation, described in the next case, can be used.

Therefore, the mediator will commence with the facilitative model in mind for purposes of bringing the parties together to map out, work together and construct their own outcome. If, however, the mediator finds that this is not working and parties are not functioning properly together to find a sustainable solution, he/she or they can choose to turn to the evaluative model. For a practical insight into mediation in general and the different types of mediation techniques, read Michael Doherty, ‘Conflict Resolution and Mediation Sills’ Mediation NI (2017).

In the event that the mediator is not aware of the current situation in relation to racism and xenophobia, the treatment of refugees and/or youth criminality, he or she will do background research by gathering information on the situation. This will include interviewing third parties such as other members of the community and experts in order to clarify the underlying structural causes of the dispute. After gathering all relevant information, the mediator will meet with each disputant individually in order to hear their side of the story and ascertain how they perceive the reasons and effects of the conflict. The mediator will meet with the two persons involved in the initial argument as well as the others who took part in the subsequent violent episode.

After mapping out each side’s perceptions of the conflict, the mediator will establish a common session for the four students. This session will commence with the basic rules of comportment such as confidentiality and politeness and will follow with the parties setting out their aspirations and hopes in relation to what will be achieved. This session can be repeated several times until the parties:

- Conceptualise the reasons for the conflict and the conflict itself;

- Discuss underlying reasons, fears and insecurities that may exist in all parties and constitute a hotbed for conflict;

- Understand their role in the creation and escalation of the conflict;

- Consider ways in which such a conflict could have been prevented;

- Consider ways in which such a conflict does not occur again;

- Reach an agreement on how the parties wish to ‘close’ this chapter.

Given that the process is party centred, participants to the process develop communication and active listening skills which are central to tackling the particular conflict and preventing its re-occurrence. This creates a sense of understanding between each party as they will come to understand each other’s thought process and the way each party approaches the conflict and underlying themes. It must be noted that the mediator will remain impartial and independent throughout the process but, where necessary and applicable, in the construction of the reasons that led up to the conflict, the mediator can debunk several false narratives that exist in relation to asylum seekers and refugees. This will be particularly relevant if the Cypriot students demonstrate a fear or anxiety towards asylum seekers and refugees due to misinformation. In addition, the mediator could apply the use of logical analogies and empathy as well as citing similarities between the disputants or explaining the role and advantages of interdependency between refugees and citizens in society.

In order not to re-aggravate the student who initially started this conflict as a result of prejudice, intolerance, racism and/or xenophobia and for purposes of ensuring a sustainable approach, it is necessary for the mediator to adopt an attitude of blame but to mobilise on this opportunity to educate the Cypriot student who started the conflict on the danger of underlying prejudice and intolerance.

Results

This non-judicial form of dispute resolution, which if conducted properly and if the parties involved have at least some intention of the conflict being addressed, will be beneficial on a micro (interpersonal), meso (group) and macro (community) level.

CASE STUDY II

Background

This is a dispute between a Turkish Cypriot and a Greek Cypriot. The generalised tension in Cyprus between the two communities has led to social, political and economic disputes between both communities. Although there have been discussions to unite the Island, little progress has been made to this effect. In this case, sheep belonging to a Turkish Cypriot in the North have mistakenly crossed over to a Greek Cypriot’s land in the South. This has been interpreted as a type of aggression on the part of the Turkish Cypriot by the Greek Cypriot thereby leading to a dispute. Usually, in such cases which involve disputes between a Turkish Cypriot and a Greek Cypriot, a UN Peacekeeper is likely to play the role of Mediator; as UN peacekeepers are usually foreigners and a risk of a suspected conflict of interest which might arise from a mediator being a member of one of the communities related to the dispute is unlikely to be found.

Resolving the Dispute

In this case, the Mediator will have to meet with the parties separately in order to understand the situation at hand. Furthermore, the mediator will obtain peripheral information from third parties and through further research on the issue. Since the mediators in such cases are usually UN Peacekeepers, who are already conversant with the background issue regarding Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots, there might be no need for extensive research on the part of the Mediator. Nonetheless, as stated earlier, research regarding the specific dispute at hand needs to be carried out. After getting an understanding of the situation, the mediator will invite both parties, separately, to express their position, ideas and problems. The mediator will judge whether he or she can use the facilitative or evaluative models discussed above or whether, due to prolonged tension between the two communities, shuttle mediation could be used.

Shuttle mediation is implemented when parties do not agree to meet face to face. This occurs when there ‘is a lot of anger about, feelings are very high or one or other party feel that they just cannot face the other party under any circumstances.’ As can be noticed in this case, the disputants do not necessarily have to meet with the Mediator since, due to the fragility of the relationship between the communities, the Mediator could meet individually with the disputants until the end goal is achieved, that being the sheep safely returned to the Turkish Cypriot

This technique was used in the Parade disputes in Northern Ireland. Given that the aforementioned case could be complicated by the fact that it is affected by endemic prejudice resulting from the social and political conflict between the two communities, the shuttle technique could be relevant.

Accordingly, if the parties do not want to meet each other and discuss but do want the problem to be solved, the mediator will work with each side independently. Given that the other party is not present during this process, it is paramount that the mediator is absolutely and unequivocally neutral so that neither side is concerned about possible impartiality. The mediator then works with both independently; presenting points to each side. As well as important skills of mediation, such as negotiation and re-conceputalisation of the conflict and its structural routes, the mediator could use empathy and, in this case, personalised analogies when speaking with the Greek Cypriot on returning the Turkish Cypriot’s sheep. The mediator will carefully explain to the Turkish Cypriot how such issues could be perceived as provocation through logical analysis and by providing examples of similar situations. This way, an understanding can be created. All these will be done with third party assistance to ease any tensions, and the sheep could then be given to the Mediator to return to the Turkish Cypriot.

Results

Such mediation will set a precedence of tolerance between both communities, especially in places such as Pyla, where members of both communities still co-exist today

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY

This chapter will look at the methodology and process of Social Mediation.

PREVENTION

Social Mediation as a preventative tool rests on certain principles. These include, firstly, voluntarism, whereby, as a preventative tool, Social Mediation is commenced freely and terminated freely whenever the parties and the mediator so wish. Secondly, neutrality, whereby Social Mediation seeks to ensure that mediators have no connections or relations with the participating parties, consequently making mediation a balanced process based on equality and impartiality and, thirdly, confidentiality, which is a principle whereby the process remains as confidential as possible. Lastly, the principle of good faith, whereby Social Mediation is a preventative tool aiming to preserve the idea of mutual understanding and respect between parties throughout the process.

When seeking to PREVENT a conflict in a potentially high risk area, a social mediator will:

Identify the issues that underlie the functioning (or not) of the particular community and tackle these issues, such as prejudices, stereotypes and misconceptions. The preventative actions seek to overcome prejudices and strengthen community ties through, for example:

- Community and group activities;

- Intercultural activities;

- Awareness raising activities.

When seeking to RESOLVE a conflict, the social mediator may opt to conduct some of the preventative activities (according to the level of conflict). There is a possibility that the conflict level is so high that there is no possibility of using the above actions or limited use of such actions.

The activities seek to facilitate cohabitation, overcome underlying issues (to the extent possible) and also develop the way in which conflict is faced by people through, for example, the promotion of skills pertaining to:

- Continuing preventative actions (according to the climate) and for purposes of tackling the underlying issues such as stereotypes and prejudices;

- Positive and open dialogue on an interpersonal and community level;

- Resolution of conflict in a non-violent manner.

In the resolution of a conflict, the parties come together voluntarily in the presence of one or more mediators (according to the size of the group) to discuss:

- The conflict itself (e.g. a neighbourhood fight)

- The underlying structural causes of the conflict (prejudices, intolerances, tensions between groups)

It is paramount that it is the parties themselves who deconstruct the conflict and its underlying causes and create an alternative. The involvement of parties has been conceptualised as a form of ‘democratic participation.’ The process itself is empowering for all involved and, particularly, for those who are members of the ‘minority’ group but also the element of user-centrality facilitates the sustainability of the outcome. Throughout the entire procedure, the mediator remains independent and impartial, acting as a facilitator for communication, exchange and discussion. He or she does not deconstruct the conflict or offer a solution to it. This is for the parties to do.

When seeking to REHABILITATE the parties of the conflict and/or their respective groups and/or the community, the social mediator may opt to:

- Continue preventative actions (according to the climate) for purposes of tackling the underlying issues such as stereotypes and prejudices;

- Embed community members with the skills and attitudes necessary to face the conflict in a positive and non-aggressive manner.

A social mediator must:

- Develop and implement activities only if the community needs him/ her and wants his/her presence;

- Get to know the members of the community, the community leaders and any other actors;

- Develop an empathetic stance to the persons, groups and communities involved. For this to happen, the mediator must invest time and energy in developing relations with the members and key actors so as to become ‘accepted’ as the mediator, whilst simultaneously retaining his/her neutrality and non-bias;

- Construct effective links with relevant actors and agents;

- Consider and learn about the structural and infrastructural dynamics of the community.

Once the mediator has established effective links with the community, its members and any relevant actors, the mediation process goes through four phases:

- Identification of issues

- Consideration of alternatives

- Selection of an alternative

- Development of an action plan so as to achieve that alternative

It is paramount that all four phases occur with the community and its members so as to ensure that the process is needs-based and needs-responsive.

1. Identification of issues

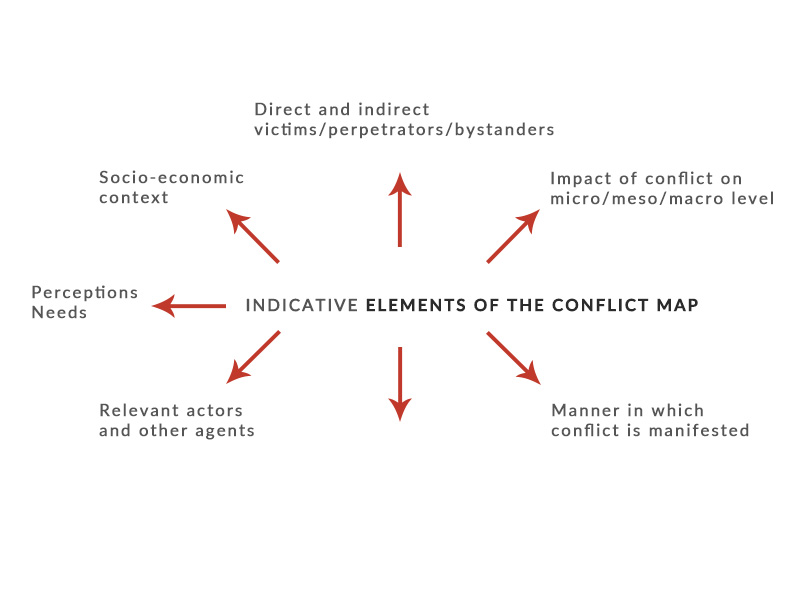

- Develop a conflict map so as to clarify the situation and contextualize his/her work;

- Develop another conflict map in collaboration with the community members of each conflicting part so as to learn about the way the community members themselves conceptualise and understand the conflict. As well as facilitating the conceptualisation of the conflict from both sides, this activity is also one that can promote dialogue and discussion amongst community members as they are working together on this project (i.e. map drawing) simultaneously discussing their sides of the conflict together;

2 & 3. Consideration and choice of an alternative:

Using a method such as structured dialogue, the social mediator must prompt the community members themselves to realise that the situation (pre, current or post) conflict needs to be improved so as to prevent, eliminate or manage conflict (according to the temporal framework) and, for this to occur, a selection of alternatives needs to be considered. Once a selection of alternatives has been considered, the persons participating in this process will choose one alternative. This process is complicated since participants:

- Must be flexible in reaching an alternative in which all sides and interests are satisfied;

- Must develop a sense of shared responsibility for the conflict instead of blaming/scapegoating the other side of the community;

It is possible that high levels of conflict and/or antagonism and/or fear of giving up their position will not allow this part of the process to occur effectively. In such situations, the mediator may engage with each side alone before bringing them back together for a discussion on alternatives. These are known as ‘caucus sessions.’ Mediators must conduct these sessions with care so as to eliminate the possibility of appearing biased to a particular side given that not all members or their representatives are part of this process.

All subsequent actions designed and implemented will aim at reaching that alternative and also contributing to the creation of the general spirit of inclusion and social justice which is, by default, an objective of Social Mediation.

4. Plan of action

Following the conflict map, the social mediator in collaboration with the community, its members and relevant actors must set out a list of possible actions and incorporate, where relevant and possible, the community itself in the development of ideas for action.

In all the above activities, the key rule is that the mediator takes the neutral role of a facilitator of communication, encouraging positive dialogue, co-developing projects and activities which are (designed if applicable) and implemented by the members of the communities. In addition, the mediator must place particular emphasis on facilitating reflection of the activities and actions taken as this process will allow for an in-depth approach with potentially sustainable results. It is not sufficient that an activity occurs, it is necessary that all persons involved, with the assistance of the mediator, reflect and evaluate on how the activity has had an impact on them, their groups and the community as a whole and how it has contributed to conflict resolution.

Ideas for actions:

Raising awareness and increasing inter-disputant empathy

- Awareness raising activities on issues relevant to the dispute and particularly linked to the stereotypes and prejudices underlying the conflict. For example, holding a ‘refugee week’ in the community;

- Common intercultural activities to include an exchange of customs, food, music and cultural practices so as to learn about one another and to overcome potential or actual stereotypes;

- Other cultural activities to be held for all members of the community such as film screenings, theatre shows and other cultural activities which provide a common space for the members to come together and overcome their prejudices and conflicts.

Training and Empowerment

- Training of community members on mediation so as to develop knowledge and skills in the community itself for peaceful and sustainable conflict-resolution;

- Implementation of non-formal educational activities on issues pertaining to, for example, human rights and citizenship so as to endow members of the community with the knowledge, skills and attitudes for the creation of a peaceful and just community.

Positive Dialogue

Structured dialogue with members of the community (only) or with relevant actors and agents for, inter alia, conflict mapping and development of alternatives.

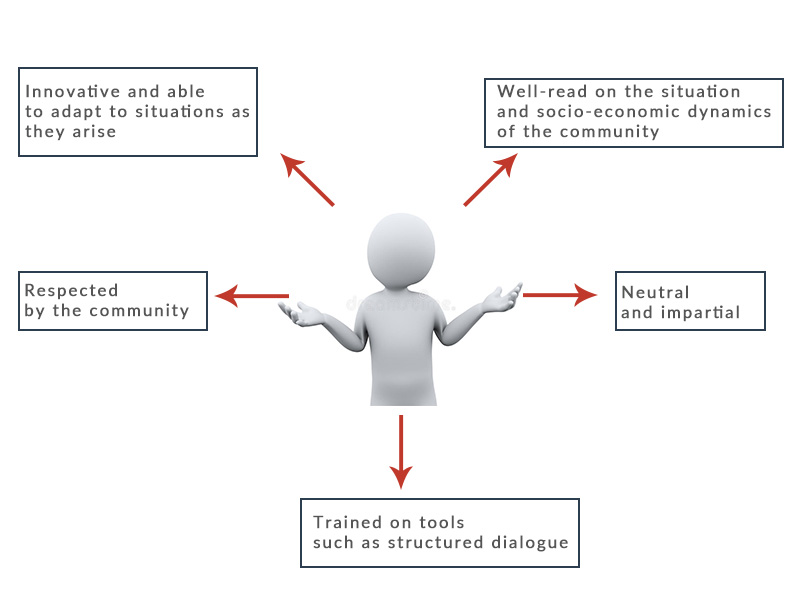

To achieve the above, a mediator must be:

HANDBOOK TEAM

Authors (short biographies and testimonials)

In alphabetical order:

Amura Daniela

My name is Daniela Amura. I am in the second year of my LLB studies at UCLan Cyprus and am an intern at ICLAIM. I am half Bulgarian and half Palestinian. Since the day I was born, I was given the opportunity to look at this world from two different points of view, which despite their differences tended to blend perfectly, leaving me with a piece of art which I had to learn how to appreciate. As a member of today’s modern society and as a person who has observed the suffering of this world, I have built the belief that conflicts which arise from the reflections of the differences embedded in the creation of opposing societies can all contribute to the development of better understanding. The world has the capacity to embrace all of these differences, simply if it is given the chance to look at these differences as building blocks. As an individual with Palestinian origin who has witnessed the ignition of the Arab Spring, and who currently lives on the divided Island of Cyprus, I see the constantly evolving need for different integrative mechanisms. Conflict resolution tools, such as mediation, have the power to build bridges and connect differences on the same table by reminding individuals of the essence and degree of reasonability of a conflict. The current research and ICLAIM will give me the opportunity to contribute to the emphasis on the constructive potential of differences and to promote an alternative conflict resolution mechanism such as mediation.

Bankole Oluwatodimu

I am a final year LLB student at UCLan Cyprus and an intern at ICLAIM. I am a co-founder of the Humanitarian Aid Program which is a non-governmental organisation that raises donations for refugees and the less privileged within our society. Also, I am a human rights activist for the No Hate Speech Movement which is a campaign founded by the youth sector of the Council of Europe to tackle hate speech and enhance human rights education. As an activist, I develop effective and non-violent tools, for example, bookmarks, which contain counter narratives and alternative narratives that can be used to combat hate speech. Also, I develop mechanisms by which people can be educated on how to use these narratives and methods effectively within their organisations and communities. Previously, I have worked as a child counsellor to vulnerable children in Nigeria and a co-opted protection officer for children and vulnerable adults in Cyprus. Also, I briefly worked as a board member with the African Chapter of Jobs without Borders which required me to direct ambassadors and volunteers on how to give humanitarian assistance to young people in Africa. I currently work as a volunteer social worker for refugees, asylum seekers and migrant workers and a human rights trainer. In addition, I assist in teaching basic English language to refugees and asylum seekers in order to help with their integration into society.

Eljedi Malak

I am a final year LLB student at UCLan Cyprus and an intern at ICLAIM. I am the co-founder of the Humanitarian Aid Program (HAP), which for the past year has focused on helping refugees within Cyprus by collecting donations and spreading awareness about the ongoing refugee crisis via social media. Accordingly, working with the organisation has enabled me to develop the skill of effectively communicating with both refugees and staff by maintaining a significant degree of impartiality. Likewise, being fluent in Arabic was an advantage since it made it easier to reach an understanding with the refugees, which places me in the position of undertaking effective mediation processes within the refugee community. Additionally, because I grew up travelling, I have been able to experience and understand diverse conflicts within various communities. For example, I was able to witness the conflict between the Sunni and Shia Muslims in Kuwait first-hand. I acquired the ability to give an unbiased third party view on the conflict. I could conclude that most of the time these conflicts would arise due to miscommunication between the parties leading to misunderstandings. Thus, mediation is a strong tool to end such conflicts amicably. Taking part in this project enhanced my knowledge on mediation, which I could then introduce and implement within the Libyan community where mediation is not as popular. Furthermore, mediation could limit the ‘compensation culture’ within several countries.

Taifour Machi

I am a second year LLB student at UCLan Cyprus. For the past year, I have been interning at a probate firm. This has not only expanded my legal knowledge but has also led me to realise that I want to follow a legal career in family law and mediation. I was led to that decision after witnessing a great many advantages provided by mediation. To begin with, mediation creates an informal environment where people are free from the feeling of intimidation and being interrogated and are actually there because they are able to receive what they came for, that is guidance and help without pressure and awkwardness. Furthermore, Social Mediation is designed to preserve individual interests while strengthening relationships and building connections between people and groups and create processes that make communities work for all of us. Thus, at the end of the day, there is common ground, not just a winner. During Social Mediation, you get to guide the participants through a collaborative problem-solving process during which participants can develop solutions that meet their needs.

Toncheva Vaneva Toni

I am a second year LLB student. I was born in 1997 and my roots and parents are Bulgarian but I grew up in the Republic of Cyprus and have been here since 2006. I have witnessed the effects of difference in a school environment, in relation to bullying and the prejudice which is associated, even by children, to others of a different background. I believe that Social Mediation is a tool that can tackle these issues in a sustainable and peaceful manner. I enjoy learning about human rights and have participated in several activities such as the ‘Human Rights Education’ workshop organised by Aequitas and co-founded by the European Commission to promote and create a just society .Also, I am interested in the principle of Rule of law and equality and have attended seminars such as ‘History of Diplomacy’ , ‘Democracy’ lectures and ‘The Rule of Law in Cyprus and the Lessons of History: Linking the Past with Today and Tomorrow’, I like to develop my knowledge on non-violent tools and alternative narratives in everyday life. I promote these mechanisms by which people can be educated in order to learn how they can effectively change their behaviour and actions upon other human beings and nations. In addition I have an internship as a social intern at Rolesa legal education organisation which is working toward an intelligent globalized platform. Also I attend trainings on Mediation which help me to create better perspectives on legal issues such as the European migrant crisis.

Supervisors:

Dr. Natalie Alkiviadou, Director ICLAIM: Natalie has over ten years experience in working with civil society, educators and public servants in the framework of training and capacity building on human rights and related themes. Her research expertise lies in EU Law and human rights law with a focus on hate speech, hate crime and right-wing extremism. Within her capacity as director of AEQUITAS, an NGO working on human rights education, she has drafted handbooks, strategy papers and shadow reports for projects funded by the Anna Lindh Foundation, the European Commission and the European Youth Foundation, on themes such as the rights of domestic workers in Cyprus, hate crime and extremism in young people and ENAR’s shadow report on Afrophobia. Recently she undertook an accredited conflict management and mediation skills course to develop her dispute resolution skills as a necessary companion to her current research interest and knowledge transfer activities, embedded in ICLAIM for the benefit of the wider community.

Professor Stéphanie Laulhé Shaelou, Founding Member and Director ICLAIM: Stephanie has over 15 years of experience in researching and disseminating primarily EU law-related knowledge to young people but also to civil society representatives and professionals in the framework of teaching, training, networking and professional development. Her PhD published in a monograph, as well as many of her other publications, deal with Cyprus’s full integration into the EU and economic growth as a model of European integration. Stephanie has also extensively researched and published on crisis-related situations such as the financial crisis, the protection of fundamental rights or State good relations, including in the Cyprus context. Recently she undertook an accredited conflict management and mediation skills course to develop her dispute resolution skills as a necessary companion to her current research interest and knowledge transfer activities, embedded in ICLAIM for the benefit of the wider community. Professor Laulhé Shaelou is also a registered mediator with the Ministry of Justice and Public Order of the Republic of Cyprus.

Reviewers:

Dr. Nasia Hadjigeorgiou, Lecturer in Human Rights and Transitional Justice at the School of Law, UCLan Cyprus. Nasia’s research interests focus on the protection of human rights and their use as conflict resolution tools in post-violence or post-conflict societies. She has published on the promotion of reconciliation and the building of peace in such societies, whether through the use of legal tools or alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. She is currently working on the publication of her first monograph, entitled Protecting Human Rights and Building Peace in Post-violence Societies: An Underexplored Relationship (forthcoming 2019, Hart Publishing). She has, moreover, taught on a range of related modules on the LLM course, such as ‘Peacebuilding and the Law’ and ‘Conflict Resolution and the Law’.

Dr. Katerina Antoniou, Resident Member ICLAIM: Katerina is a lecturer at the University of Central Lancashire Cyprus and a course leader for the BA (Hons) in Hospitality and Tourism Management. She specialises in peacebuilding and conflict resolution research. She holds a PhD on international peacebuilding from the University of Central Lancashire, particularly examining group membership and interaction among peacebuilding professionals in Cyprus. Additional research interests include securitisation, social identity, intergroup contact, and dark tourism. Katerina has received training on higher education and cross-cultural facilitation. She has also been involved in a variety of non-formal education initiatives, including youth empowerment workshops and intercommunal activities, and is a Fulbright Alumna. She holds a BA in Political Science and Economics from Clark University, Massachusetts, and a MSc in International Relations Theory from the London School of Economics. She more recently undertook an accredited conflict management and mediation skills course to develop her dispute resolution skills as a necessary companion to her current research interest and knowledge transfer activities, embedded in ICLAIM for the benefit of the wider community.

Nadia Kornioti, Research ICLAIM: Nadia is a PhD candidate at the School of Law, UCLan Cyprus. She has extensive work experience with a number of Cyprus-based and international organisations, primarily in the areas of Migration, Asylum, Reconciliation, Transitional Justice and Peace Education. She is also a member of the Cypriot Branch of the International Law Association and a member of the association’s international committee on ‘Human Rights in Times of Emergency’.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

Social Mediation is a process which empowers all those who are directly and indirectly affected by community conflict to take part in addressing this conflict at a pre, current and post-conflict stage. The particularly significant role played by the community members in determining the nature of conflict, as discussed above, and creating ideas on how this conflict can be addressed facilitate sustainable and long-term results. Moreover, Social Mediation does not only address the conflict itself, for example, street violence, but also the underlying and deeply rooted reasons. It also allows participants to reconceptualise the meaning of a community in a more inclusive fashion, embedding strong foundations for future peaceful co-existence. Also, Social Mediation methods also develop significant skills in participants such as those of conflict resolution and positive communication. However, it may be particularly difficult for Social Mediation, as a non-intrusive and voluntary process, to work effectively in communities with deeply rooted prejudices and/or deeply complex and long-term conflicts. In such settings, more time and effort must be taken by the social mediator to overcome stagnant and embedded structural problems and issues.

We would like to thank César Arroyo López for the support and training he offered the team in preparation for this handbook.